“Hi Stretch!” I turned in the driver’s seat. ‘Your chariot awaits.”

“Hey Michelle.” he chuckled, crouching his 6’5” frame through the side door of the red shuttle van, taking the bench seat behind me. “How’s your day going?”

“Good so far. Finished another row on Brandon’s hat. I think I’m starting to get the hang of this knitting stuff.” I laughed and held up the pile of yarn and needles from my lap. “Did you hear some Adélie penguins were down at the runway? And the Emperor penguin is still hanging out in the same spot on the road.”

“Oh, really? I hadn’t heard about the Adélies.” He laid his water bottle and red grease-stained parka on the seat next to him and tried to get as comfortable as one could while wearing insulated Carhart bibs and white bunny boots that resembled Mickey Mouse shoes. “Did the fire department have to shoo them off the runway?”

“Not that I’ve heard yet. Last I saw they were over by the supply shack. I think one was trying to play frisbee with some of the supply crew.”

“I don’t doubt it,” he said, laughing. “They’re so curious.”

I glanced at the clock on the dash. “Well, looks like it’s just you and me this trip,” I traded the partially finished hat for my purple water bottle on the seat next to me, took a quick sip, and put the van into drive. We inched away from the sign reading “Derelict Junction”. The aptly named town bus stop was a makeshift wooden structure situated in the parking area between the galley and the dorms.

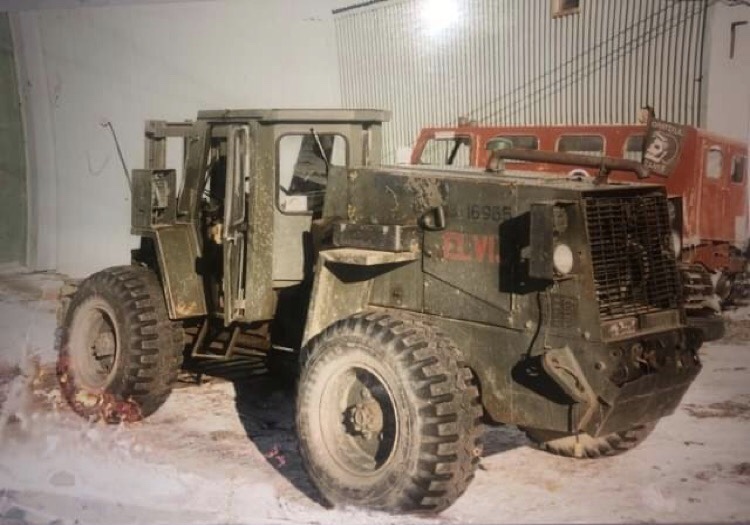

Driving through town, we navigated the after-lunch rush of people, trucks, dozers, and loaders. Elvis, one of the little “green pickle” forklifts scooted through the stop sign in front of us, carrying a dumpster labeled “Burnables”.

Soon the pedestrians, vehicles, and buildings faded away, replaced by massive silver fuel tanks surrounded with large rocky berms. We continued to drive up the hill through the pass leading out of town.

Observation Hill, or Ob hill as it’s known, was to our right. Its steep, natural pyramid shape stood stoic in remembrance of those who came before us. A nine-foot wooden cross, erected in 1913 for Robert F. Scott and his men, who died on their return trip from reaching the South Pole, rested atop the 750-foot hill.

T-site, short for Transmitter Site, sat on the hill to our left. It was a restricted area with a small building surrounded by several large antennas. The exact reason for it was still unclear to me and the closest I had ever been was to drop off a utility technician at the entrance.

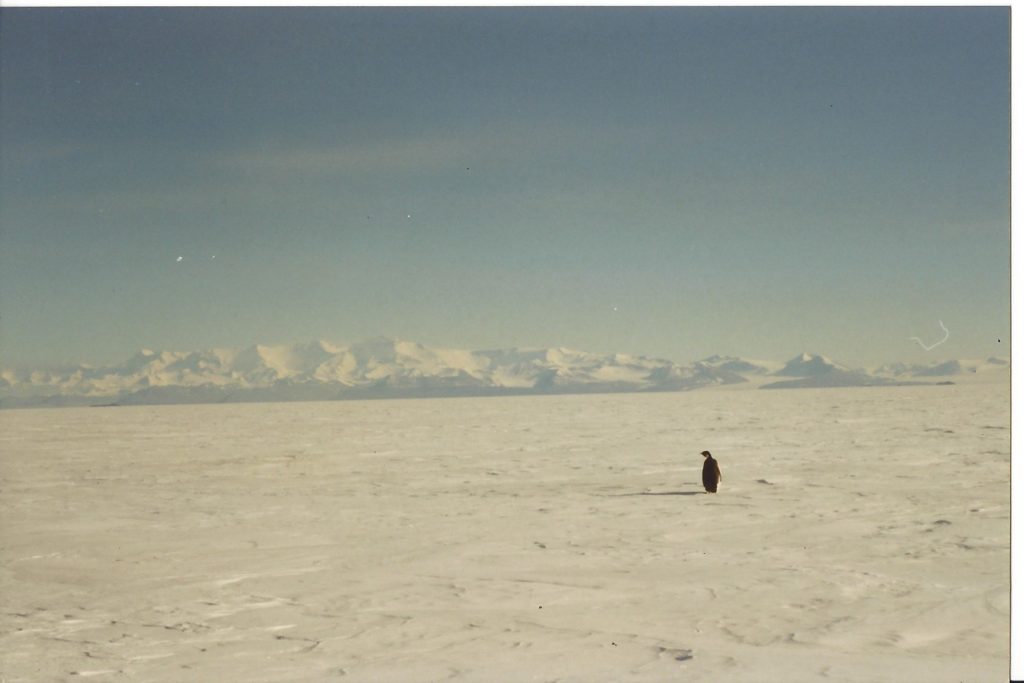

I pulled my sunglasses down as we rounded the edge of the pass, greeted by a blinding view of the McMurdo Ice Shelf. The seemingly endless permanent ice separated our home on Ross Island from the main Continent of Antarctica. So expansive was the blue sky that even the mountains rising in the distance were in danger of being swallowed up by the sheer vastness of it all.

“What are you doing out at Willy today?” I broke the comfortable silence, keeping my eyes on the narrow rocky road which now hugged the hillside.

Through my rearview mirror, I caught a smile as Stretch leaned forward in his seat. “I’ll be driving back and forth in the loader, packing the road down for ya. It’s the road to nowhere for me today.”

Stretch worked for Fleet Ops and they were responsible for maintaining all the roads and runways. His nickname had come from his first year down. He had been bulldozing snow off the runway with a Cat D8, called a Stretch 8. To keep things simple on the radio his foreman started calling him Stretch. And it stuck.

“Nice,” I grinned, “but don’t get me started on going nowhere.”

“Oh? What’s up?” His deep voice was always so calm and gentle.

“Nothing…” I shrugged, and waved a hand in dismissal.

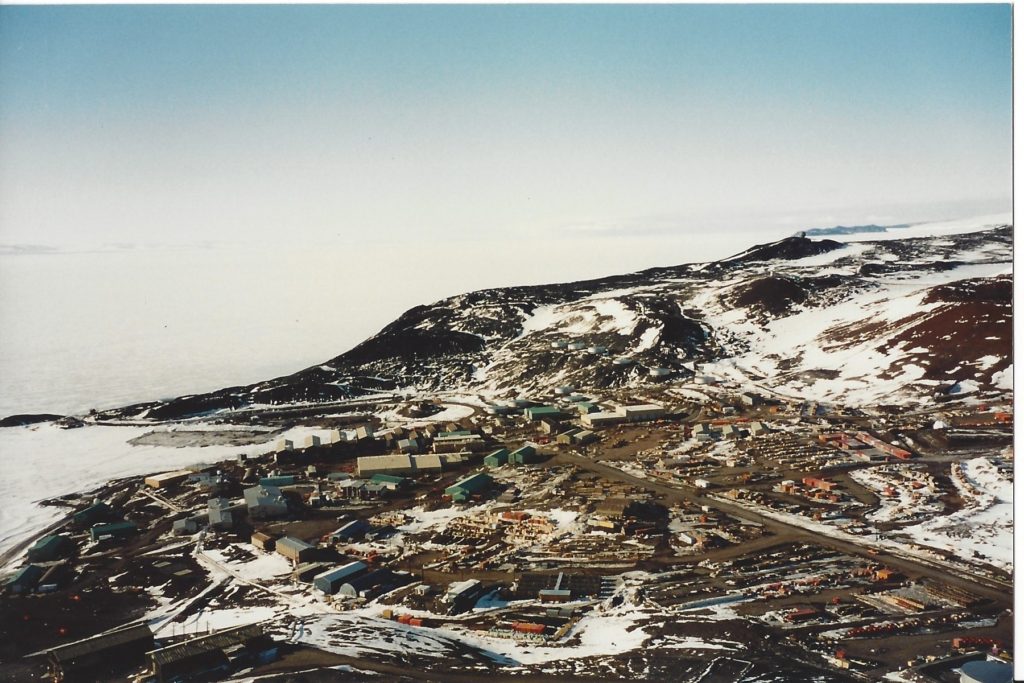

Scott Base, the New Zealand Antarctic research station, came into closer view as we approached the bottom of the hill. It sat just two miles from our home at McMurdo Station. The Kiwi’s, as they’re affectionately referred to, had a great little place. The handful of green buildings that made up their station always looked so neat and tidy.

It was a drastic contrast to McMurdo’s hodge-podge of over 100 buildings of various shapes and sizes, with colors ranging in military green, brown and tan. There were also hundreds of orange shipping containers and wooden pallets littered between.

“Well, it doesn’t sound like nothing.” Stretch’s tone was empathetic. We’d been coming here for several years, and although we weren’t close friends, we had a familiar respect for one another. “What happened?”

“I know I shouldn’t complain,” taking the opportunity to vent, “but I found out today I don’t get to go on a boondoggle again this year. It’s been four years since I’ve been picked for any of them.”

Each year there were opportunities to go on a sort of field-trip out of town. We called them boondoggles, and they were a great way to break up the mundane. Some were given out by lottery, and others by the supervisors. Over the last ten years I’d been blessed by some amazing boondoggles, including a flight to the South Pole, the IMAX crevasse via Room with a View, the penguin rookery at Cape Royds, and a flight on the Coast Guard Dolphin helicopter.

“That would be disappointing,” he sympathized.

“It is! They keep passing me over for the first-year people. I get it, but after four years, I think I’ve earned another one. I need a break from Groundhogs Day.” My words lingered as I gave my full attention to the road in front of me.

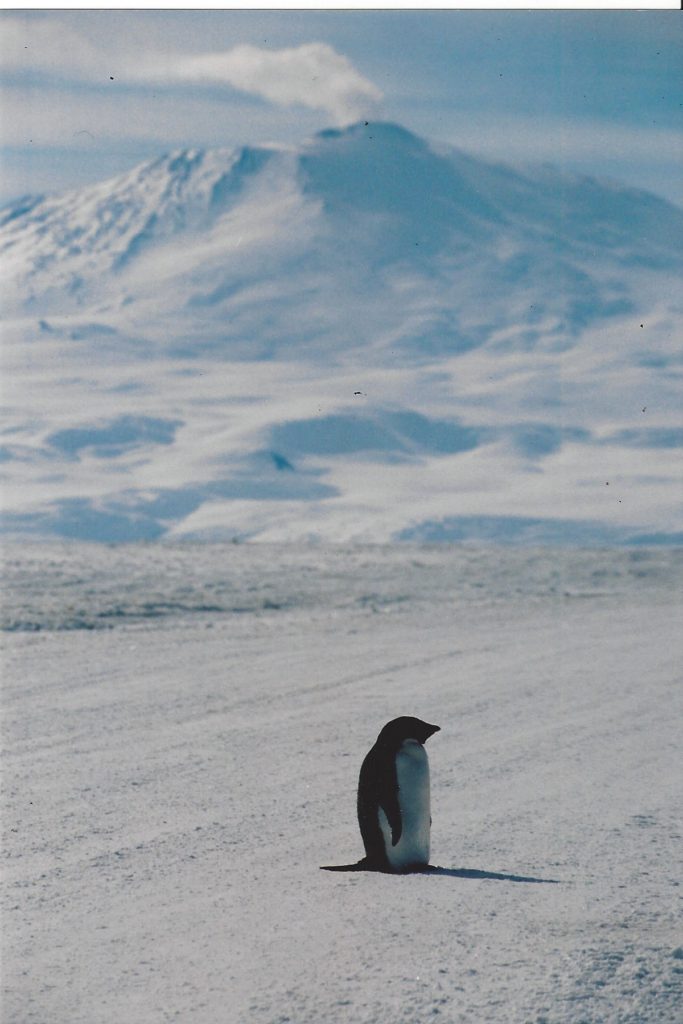

We rounded the corner past Scott Base and I slowed the van to a crawl as we approached The Transition, where volcanic rock met ice shelf. The hula girl on my dash danced violently as though to appease Mount Erebus, towering at over 12,400 feet up ahead to our left. Its white smokey plume trailed away in response.

It was the end of December, the height of summer, and the snow road was holding up well against the twenty-four-hour sunlight. The annual move of the runway from melting sea ice to ice shelf had happened just a few short weeks ago.

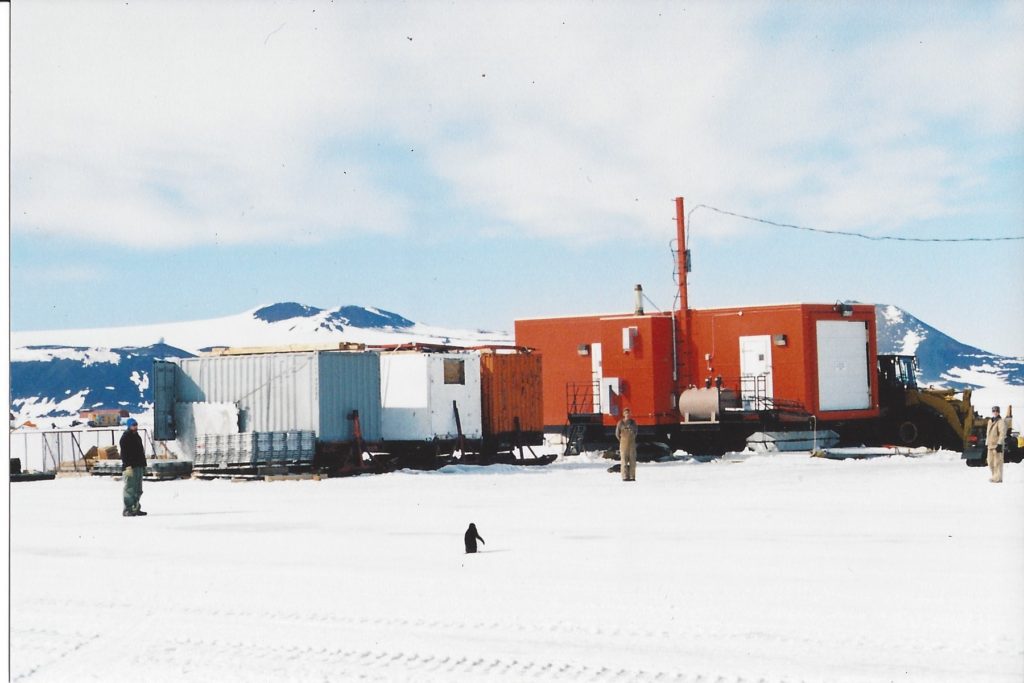

Williams Field, the permanent snow runway, sat atop 25 feet of compacted snow, 262 feet of ice, and 1,800 feet of water. Named for a Navy man who’d lost his life while helping build the first U.S. science research station in 1956. Only airplanes with skis could land there, and there were several flights a day by the Air National Guard to transport supplies.

McMurdo was the major hub of Antarctica, and science was the whole reason any of us were here. From scientists to mechanics, hairdressers to galley workers, it was a diverse group of people, but arguably the best you would ever find on the planet. And it had been my home away from home since the age of nineteen, when I followed in my father’s footsteps for a chance at adventure.

The road smoothed out and a long line of green flags marked the seven or so miles to the airfield. I glanced in my mirror and saw Stretch leaned back in his seat, gazing out the window. Possibly evaluating the condition of The Transition, or maybe trying to decide how to reply.

Before he does, I decided to continue. “I feel like since I got here in the end of September, it’s been one disappointment after the next. First, we didn’t have any ice caves this year. I heard it was because the bigwigs didn’t want to waste the manpower to find them, or the fuel to get to them. Then they kept bumping the mail off the flights. I’m still waiting to get the Christmas presents my mom sent in November.”

“Yeah, no one was happy about that decision,” he chimed in. “I hear it may be on the flight from Christchurch tomorrow. Let’s hope anyway.”

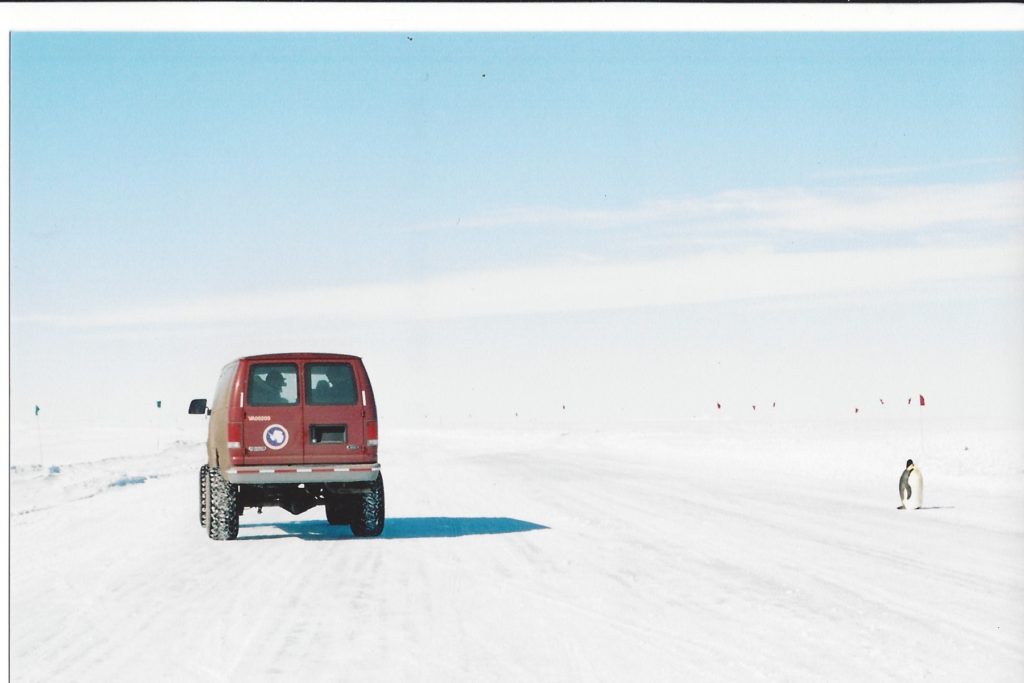

I slow the van again as we see the Emperor penguin up ahead on the side of the road. The shuttle van that left the runway for town had stopped, and a couple people in crisp, clean red parkas stood on the road taking pictures. The Emperor, motionless, seemed unfazed by the paparazzi.

“Do you want me to stop?” I interrupt the conversation. “We have a few minutes.”

“No, that’s okay.”

“Anyway,” I continued on, “now I’m hearing rumors they aren’t going to do any ice breaker cruises this year. The ice breaker was always the one thing everyone on station could look forward to. No matter what their job. All that on top of finding out there’ll be no boondoggle for me this year. It’s just disappointing. You know?”

“I do.”

“Sorry to ramble on.” I apologized, glancing over my shoulder. He now leaned forward, elbows on his knees, chin resting on his hand. “It just seems like every year they take something else away from us. Or heap on new rules and restrictions. Like over the top safety standards, to what kind of parties we can and can’t have.” I paused to take a sip from my water bottle. Antarctica, even with its miles of snow and ice, is the driest place on earth.

“Yep. I hear ya. With every new contractor it seems more freedoms are taken away.”

“Yet, we’re supposed to be happy and keep working 60 hours a week, just so some office person back in Denver can report they saved the company some money. Forget the fact that it would boost morale and help us all push through to the end of February when most of us will get to go home. And finally eat a decent meal and smell something other than diesel fumes and galley food.” I added with one final rant.

“You’re right. Things just aren’t how they used to be.” He leaned back in his seat once more. “Here’s how I see it. It’s usually not the lions and tigers that’ll get us, but the mosquitoes.”

I contemplated what he said. Willy Field was up ahead, and with it an LC-130 Hercules on its approach for a touch and go landing. The skis touched down for a brief moment and the weight of his words hit me. Then, just as fast, the plane lifted off again, and when it did, the heaviness of the day lifted as well. A smile slowly spread across my face.

“I love that.” I said to him, my eyes wide with realization. “You’re so right.”

We pulled into Willy, and spied the group of Adélies off in the distance past the runway. They cheerfully bobbed back and forth, arms out on each side, running off to some unseen destination. I drove past the double row of ten or so orange and white huts on skis to the shuttle stop at the end, and parked.

Stretch gathered his things and leaned up between the front seats. He took his sunglasses off to look me in the eyes, and I responded by doing the same. “I know it’s not always easy down here.” He said. “You know as well as I that a lot of people went through heaps worse to call this place home. Lions and tigers, you might say. So, when I feel those mosquitoes biting, I remind myself just how small they really are. Not that they don’t hurt, or drive me crazy for days on end. But I try to remind myself of the big picture, and why I wanted to be here in the first place.” He gave one last smile before ducking out the door.

“Thanks, Stretch! I appreciate it.” I called out just before the door shut, and reached over for the pile of needles and yarn once more.

Without looking back, he gave a wave and was on his way.

My trip back to town was solo, and Stretch’s words ran through my head. He was right. I was letting all the little stuff pile up and block my view of where I was. Even with all the modern comforts of McMurdo, it didn’t change how much isolation could hold a magnifying glass to everything. I may feel stuck here at times, with not much to break up the monotony. But what a place to be stuck.

This time, when I reached the Emperor penguin, I decided to stop and take some pictures. He simply stood there, motionless, eyes closed, sunning himself. Taking in the moment. Oblivious to my intrusion.

Alone together, I decided to do the same, only with my eyes wide open. I turned in a circle and took in the wonder before me.

Infinite blue sky blanketed the frozen world I stood in. Ahead I could see the crevasse riddled snow that rippled down every part of Mount Erebus. It stood ageless, timeless, glorious. To my right spread the icy expanse of the Ross Ice Shelf, leading to all points south. Behind, and to my left, rose the Royal Society Mountains, ever changing with the light, and the Fata Morgana mirages. Some days they towered, reaching for the sun. Others they sank, retreating into the distance. I could see the glaciers that dripped lazily down and between the black cliffs and valleys, escaping to the frozen sea below. Heaving and buckling, they worked their way to open water. To freedom.

This was an inherently beautiful place. And how grateful was I for that reminder.

6 Comments

Leave your reply.